Part I - The Valley of Mexico

|

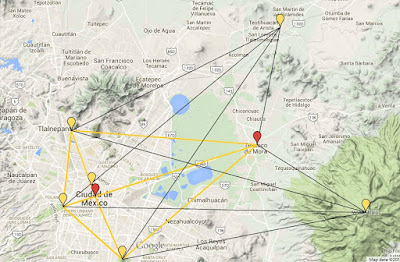

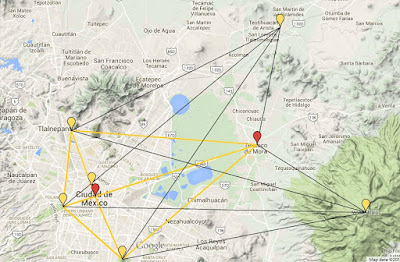

| An overview of the system of alignments of ancient sites that we have discovered across the Valley of Mexico. The great Aztec capital of México-Tenochtitlan occupies the most privileged spot in this scheme, at the intersection of two major alignments. Texcoco, Chapultepec, Tenayuca and Cerro de la Estrella represent equally important focal points in the same scheme. [Reconstruction by Author, courtesy Google Maps] |

“A great, scientific instrument lies sprawled over the entire surface of

the globe. At some period, thousands of years ago, almost every corner of the

world was visited by people with a particular task to accomplish. With the help

of some remarkable power, by which they could cut and raise enormous blocks of

stone, these men created vast astronomical instruments, circles of erect

pillars, pyramids, underground tunnels, cyclopean stone platforms, all linked

together by a network of tracks and alignments, whose course from horizon to

horizon was marked by stones, mounds and earthworks”

[John Michell, The New View over Atlantis,

Thames & Hudson, Reprinted 2001]

This is the first part of a

series of articles on what will be considered by many as a very controversial

subject. The topic is that of the alignment and placement of ancient sites. There

are many theories and speculations on why a particular location was chosen for

the placement of ancient pyramids, ancient temples and sanctuaries,

ranging from Giza’s Orion correlation theory to New Age

beliefs in the existence of such things as ley lines and

Earth energies.

A

number of studies and the advances in the still relatively new discipline of

archaeoastronomy have revealed important elements of the connection between the

ancients and the Sky. Nevertheless, when this approach is applied outside of a single site or

landscape feature to encompass multiple ancient sites (as in the case of the

Egyptian pyramids or the ancient city of Angkor, in Cambodia), the results are,

at best, controversial.

Even

more controversial is the idea that the placement of ancient sites, even over

very long distances, would be ruled by geodetic or mathematical proportions having little or no connection at all with the local geography or other strategic reasons usually advocated for explaining the location chosen for the founding of a city or a temple.

Geodesy,

that is the science of measuring of the Earth, is not something commonly ascribed to ancient civilizations. The accurate

determination of latitude and longitude has only been possible in relatively

modern times, with the invention of precision chronographs. While latitude can

be calculated with sufficient accuracy with the help of a quadrant or

astrolabe, by observing the altitude of the sun or of certain “fixed” stars above the horizon, the problem of longitude

remained without a solution until the invention of the marine

chronometer in 1773. [1]

Without

such knowledge, establishing a “grid” or

network of ancient sites over a large enough area would have been highly

unpractical, if not impossible. This is why such a theory of long-distance

alignments of ancient sites – which would moreover need

to take into account the curvature of the Earth or some advanced surveying and

projection techniques believed to be the exclusive domain of modern science

- is nowadays utterly dismissed as a

wishful fantasy.

This often turns into a circular argument. Because no

ancient civilization clearly possessed the scientific or technological

instruments required to achieve such precision alignments, then any alignment must be the product of chance or

coincidence. This is, not to speak of the reason why

ancient civilizations should have deliberately placed their sacred sites along

a grid or system of geodetic and landscape alignments of some sort. More on this

later.

Three Pyramids and a “Star” Mountain

|

| This was the likely aspect of the great Aztec capital of México-Tenochtitlan at the time of the arrival of the Spanish Conquistadores in 1519. A city of 250,000, larger than any Western European city at the time, built on an island in the middle of the lake of Texcoco. Its ruins lay buried underneath present day Mexico City, while even the lake has succumbed to the growth of the modern-day Mexican capital. [La Gran Tenochtitlan, original painting by Miguel Covarrubias, Museo Nacional de Antopologia, Mexico City] |

Ancient Mexico is an excellent

ground for the study of ancient alignments. Not only do we find a continuity of

civilization and beliefs going back thousands of years, from the Aztecs,

Toltecs, Maya and Teotihuacan, down to the mysterious Olmecs; but we also find

more pyramids than in any other Country in the world to verify such a theory (there are no accurate estimates, but the number might easily be in the

thousands).

The

Valley of Mexico, with its vast flat plain once occupied by the ancient lake of

Texcoco and surrounded by high mountains, will be the perfect setting to verify

our theory of alignments.

When

drawing on a map the major ancient sites around the Valley of Mexico, almost immediately an

interesting pattern starts to emerge.

There are three major Aztec pyramids

within the boundaries of present day Mexico City: these are the Templo Mayor of México-Tenochtitlán, the Templo Mayor of Tlatelolco and that of Tenayuca.

All

these constructions share very similar characteristics: they were built around

the same time period, between the XIV and the early XVI Century AD, and were

all subject at some point to Aztec rule, erected by people sharing a similar

system of myths and beliefs. They all consist of a large pyramid platform,

surmounted by a double sanctuary and enclosed within a sacred precinct. Let me

state this again: These are the three largest pyramids within present day

Mexico City, and are virtually identical in construction and design [2]; yet, no one has

apparently noticed (up to this day), that they are also very precisely

aligned among each other.

Let’s

take a closer look:

Tenochtitlán

|

| A model reconstruction of the Templo Mayor of México-Tenochtitlan, from the Museo del Templo Mayor. One of the major archaeological discoveries of the 20th Century, this ancient pyramid had laid buried for almost 500 years underneath one of Mexico City's busiest squares. Excavations began in 1978, and are still ongoing. [Museo del Templo Mayor, Mexico City] |

The great Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán was built on an island in the center of the

lake of Texcoco, subsequently enlarged with the construction of artificial

dykes and canals. At the very center of the City, within the sacred precinct,

was the great Teocalli, the Templo Mayor, with its twin sanctuaries dedicated to the

gods Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli. Built as a massive pyramid, the temple had at

least seven stages of construction, dating from 1337 to 1521 AD. At its peak,

the temple measured 100 by 80 meters at its base, and reached between 45 and 60

meters in height. Its impressive ruins, discovered in 1978 after centuries of

abandonment and deliberate destruction, are still one of the major tourist

attractions in downtown Mexico City.

Tlatelolco

|

| The ruins of Tlatelolco, in present day Plaza de las Tres Culturas. Archaeological excavation have revealed the main ceremonial center of the city that was the sister twin of México-Tenochtitlan and rivaled with it in power and splendor. [Photo by Author] |

|

| After the conquest, the Spanish built a large church and a convent, named after the Colegio de Santa Cruz, on the site of the former Templo Mayor of Tlatelolco. The ruins of the massive pyramid still bear evidence of several layers of construction, being almost identical to the Templo Mayor of México-Tenochtitlan. [Photo by Author] |

Tlatelolco was a sort of sister

city to México-Tenochtitlán, also built on an island in the lake of Texcoco. The

city itself was founded by a dissident Aztec faction only 13 years after the

founding of México-Tenochtitlán, in 1338 AD. Like the Templo Mayor

of its sister city, also the great pyramid of Tlatelolco underwent

several construction stages – at least seven, whose imposing ruins still

survive in what is today Plaza de las Tres Culturas. The last construction

stage had similar dimensions to the Templo Mayor of

México-Tenochtitlán, measuring some 80 by 70 meters at the base, and also included a double

sanctuary at the top dedicated to the gods Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli.

Tenayuca

|

| The great pyramid of Tenayuca is one of the best preserved constructions of the post-classic period in the valley of Mexico. The massive pyramid also contains the remains of at least 7 other earlier stages of construction. The great pyramid of Tenayuca, with its twin sanctuaries and double stairway is considered the prototype for both the Templo Mayor of México-Tenochtitlan and of Tlatelolco. [Photo by Author] |

|

| The base of the pyramid of Tenayuca is surrounded by a massive Coatepantli, that is, a "wall of snakes", which incorporates as much as 140 sculptured serpent heads. These sculptures were originally painted in bright colors, to indicate the different cardinal directions. [Photo by Author] |

Tenayuca was an old settlement of the Chichimecas, whose foundation might be traced back to as early as 1064

AD. The last stage of construction of this pyramid, which was likely the

prototype of all later Aztec pyramids, measured 68 by 76 meters at its base,

and also underwent several stages of construction and reconstruction (at least

eight). Also at Tenayuca, a twin stairway led to the double sanctuary on top of

the massive pyramid. Interestingly, the

pyramid of Tenayuca does not share the same equinoctial orientation as the

Templo Mayor of México-Tenochtitlán and Tlatelolco, but is rather oriented

towards the setting of the star Aldebaran, in the constellation of Taurus, 17

degrees north of the ideal East-West orientation on the day of the passing of

the Sun at its zenith. [3]

The Alignment Tenayuca – Tlatelolco – Tenochtitlán – Cerro de la

Estrella

|

| The main system of ancient alignments around the Templo Mayor of México-Tenochtitlan. [Reconstruction by Author, courtesy Google Maps] |

It is easy to realize that a

line drawn through the summit of the Templo Mayor of

México-Tenochtitlán and the Templo Mayor of

Tlatelolco would terminate exactly on the main sanctuary of the pyramid of

Tenayuca.

To

further confirm and reinforce the existence of this alignment, it should be noted that one of the major

road arteries in present day Mexico City, the Calzada

Vallejo, follows exactly this same alignment between Tlatelolco and Tenayuca.

This is not surprising, given that the modern road follows the track of

one of the ancient causeways that crossed the – now dry

- lake of Texcoco in Aztec times.

|

| A detail of the alignment along the Calzada Vallejo, which follows a straight line that would have originally connected the Templo Mayor of México-Tenochtitlan to the great temple-pyramids of Tlatelolco and Tenayuca. Note also the right triangle formed between Chapultepec, Tenayuca and Texcoco. [Reconstruction by Author, courtesy Google Maps] |

A

prolongation of this alignment towards the South-East also leads to another

very important landmark in Mexico City. This time, it is not a pyramid, but

rather a steep, forested hill called Cerro de la Estrella. Again, this can be no chance: The Cerro de la Estrella

played a very important role in the sacred geography of the Valley of Mexico,

as it is the spot where the Aztecs celebrated the New Fire ceremony every 52 years, at

the end of each calendar cycle and the beginning of a new one.

The etymology of

the name is unclear; Cerro de la Estrella

meaning “Mountain of the Star”, supposedly after a colonial hacienda by the same name built on its slopes soon after the

Spanish conquest of Mexico. The ancient name of the hill, which rises 224 meters above

the surrounding plain, was Huizachtecatl,

meaning a forested hill in ancient Nahuatl. Yet the highly evocative name of

“Mountain of the Star” could have a much more profound astronomical

significance that we do not yet fully understand.

A

pyramid was built by the Aztecs on top of the Cerro de la

Estrella, but the occupation of the site dates back at least 3,000

years. A large settlement occupied the slopes of the hill between 100 and 650

AD, contemporary with the rise of the power of Teotihuacan in the valley of Mexico, on the North-Western shore of the lake of Texcoco.

Interestingly,

the alignment would not appear to point towards the summit of the hill, but rather

deviates a couple of degrees to the West towards a little eminence on its Western slope.

In

2006, a massive pyramid was discovered on the Northern slopes of Cerro de la Estrella, measuring as much as 150 meters at its

base, one wonders what might still lie buried at this fascinating site. [4]

The picture expands

|

| The two major systems of alignments that cross modern-day Mexico City - the line Tenayuca-Tlatelolco-Tenochtitlan-Cerro de la Estrella and the line Chapultepec-Tenochtitlan-Texcoco cross at a right angle on the site of the great pyramid-temple of México-Tenochtitlán, as can be easily verified from the picture above. [Reconstruction by Author, courtesy Google Maps] |

For how interesting the

alignments we have discovered so far, these would have been certainly within the

technical capabilities of the Aztecs: The longest distance in the alignment,

that is the one between Tenayuca and Cerro de la Estrella,

is only 22.5 Km, meaning that the hill would have been within a clear line of

sight connecting Tenayuca to the great temples of Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlán. This

was even truer in ancient times, without the pollution and haze of modern day

Mexico City.

Interestingly,

the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan is located

exactly at the same distance of 11.3 Km from Tenayuca and Cerro de la

Estrella, being at the exact center of the imaginary line connecting

these two points (1:1).

And what

about the position of Tlatelolco? The great pyramid of Tlatelolco is

located only 1.9 Km from the Templo Mayor of

Tenochtitlán. That means, Tlatelolco divides the line connecting the pyramid of

Tenayuca to that of Tenochtitlán in two segments of 1.9 and 9.4 Km; the total

segment length being 11.3 Km. This means that the distance Tenochtitlán-Tlatelolco

is exactly 1:5 of the distance

Tlatelolco-Tenayuca.

And

there is more. This first alignment Tenayuca-Tlatelolco-Tenochtitlán-Cerro de la Estrella appears to be at a right angle with

another equally impressive alignment, also crossing through the Templo Mayor of México-Tenochtitlán.

The alignment Texcoco-Tenochtitlan-Chapultepec

This

second alignment connects the ancient city of Texcoco to the sacred hill of

Chapultepec, and in doing so crosses the axis Tenayuca-Cerro de la Estrella

at a right angle exactly in its center, that is on the spot occupied by the Templo Mayor of México Tenochtitlán.

The

Cerro de Chapultepec, whose summit is

now occupied by the castle built for Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico in the XIX

century, was considered sacred by the Aztecs. There the Aztec emperors had

their baths and gardens, and a temple likely existed on the summit. Several

astronomical and geodetic markers are still to be found on the high cliffs

below the castle, including some fine bas-reliefs of Moctezuma II and a giant rock

sculpture of a snake.

On

the opposite end of the alignment, Texcoco was one of the cities of the Aztec

triple alliance, together with México Tenochtitlan and Tlacopán (Tacuba). A

city of the Acolhuas, Texcoco became one of the most important cities in

ancient Mexico during the reign of Netzahualcoyotl, extending itself over 450

hectares on the shores of Lake Texcoco. The city became a major center of

learning, and has been often described as the “Athens” of ancient America;

home of poets, philosophers and astronomers, as well as to one of the largest

libraries of the pre-Columbian world. The great temple of Texcoco was

apparently second only to the one of México-Tenochtitlan, and the legendary

palace of Netzahualcoyotl, consisting of some 300 rooms and all built of

dressed stone, was still a wonder to behold at the time of Bullock’s visit in

1824. [5]

|

| An ancient depiction of the Templo Mayor of Texcoco, with its twin sanctuaries at the top, from the Codex Ixtlilxochitl , early 16th Century [Codex Ixtlilxochitl, fol. 112V] |

Very

little remains nowadays of the former glory of Texcoco. The last remnants of

the great temple of Texcoco were demolished sometime around 1880 to make

material for construction, but its location is accurately marked in XIX century

maps at a place known as “Cerro de La Simona”,

along the present day Calle Guerrero, and between the Calles Allende and Aldama. This position

allows drawing a precise alignment between the Templo Mayor

of Texcoco and the Templo Mayor of

México-Tenochtitlan, pointing to the sacred hill of Chapultepec (itself a major

natural landmark on the immediate shores of what was then the lake of Texcoco).

The alignment Texcoco-Cerro de la Estrella-Cerro del Ajusco

Something

very interesting also happens when observing the alignment between Texcoco and the Cerro

de la Estrella. A prolongation of this line points straight to the summit of

the Ajusco; the highest peak, with its 3,930 meters, within modern Mexico City

boundaries and one of the most easily recognizable landmarks in the entire

valley of Mexico (its highest point, called Pico del Aguila

or Eagle’s peak was considered sacred since ancient times, and does indeed

resemble a giant spread eagle from the distance).

The triangle Texcoco-Teotihuacan-Mount Tlaloc

Texcoco

is also at the vertex of an isosceles triangle, that if forms with the ancient

sacred sites of Teotihuacan and Mount Tlaloc. The distance between Texcoco and

Teotihuacan and between Texcoco and the summit of Mount Tlaloc is the same and

equals 12.5 Km. This is suggestive of a system of survey points or triangulation

markers.

Teotihuacan

was one of the major ceremonial centers of the classic period in the valley of

Mexico, a city whose influence extended as far as Guatemala and the Maya

region. On the other hand, Mount Tlaloc, with its 4,151 meters, is one of the

highest points in the valley of Mexico, and a sacred mountain connected with

the cult of the rain-god Tlaloc. The pre-Hispanic sanctuary on its summit is

believed to be the highest archaeological site in the world, and consists of an

imposing platform approached by a stone causeway, from whose summit the view

easily embraces the entire valley of Mexico and beyond.

Connecting the dots

|

| The two interconnected systems of alignments centered on the Templo Mayor of México-Tenochtitlan and on the great pyramid-temple of Texcoco. The lines in black are hypothetical lines of sight drawn from the holy city of Teotihuacan and the pre-Columbian sanctuary on the summit of Mount Tlaloc. These two points are equidistant from Texcoco. The apparently arbitrary placement of the Templo Mayor of Tlatelolco along the axis Cerro de la Estrella-Tenochtitlán-Tenayuca now becomes clear once a new line of sight is drawn from Teotihuacan to the Cerro de Chapultepec. [Reconstruction by Author, courtesy Google Maps] |

After

connecting all the dots, the resulting figure resembles an enormous kite,

having at its four vertices the sacred sites of Texcoco, Tenayuca, Cerro de la

Estrella and Chapultepec. The observation points of Cerro del Ajusco, Monte

Tlaloc and Teotihuacan remain outside of this figure, but are placed

symmetrically with respect to each other and to the overall figure on the

ground. The Templo Mayor of México-Tenochtitlan

occupies the center of this scheme, at the intersection of the two major

alignments.

It

is interesting to note that while the location of the great temples of Texcoco,

Tenayuca, Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco, as well as of the sacred city of

Teotihuacan, reflects a deliberate artificial construction, the natural

landmarks of Chapultepec, Cerro de la Estrella, Mount Tlaloc and Cerro del Ajusco

are prominent landscape features over which human design could have had no role.

It

was probably from the observation that the remarkable hill of Cerro de la

Estrella lies virtually at the center of the triangle formed by three other major

natural landmarks: the Cerro de Chapultepec, Cerro del Ajusco and Monte Tlaloc, that the position of all the other sites could be determined.

The

prominent role of Teotihuacan in this system of alignments suggests that at

least part of this design might date back to the time in which the great city

exerted its dominion over all of Central Mexico (that is, at least in the 2nd

Century BC), a time therefore much earlier than that of the Aztecs.

The

location of the great temple and the city of Texcoco was likely defined relative

to that of Teotihuacan (which already existed at the time), of Mount Tlaloc, Cerro de la

Estrella, Cerro del Ajusco and Chapultepec. This location is almost “miraculous” in that

it is exactly equidistant between Teotihuacan and Mount Tlaloc, and is also

found on the prolongation of the natural alignment between the Cerro del Ajusco

and Cerro de la Estrella.

The

position of the Templo Mayor of

México-Tenochtitlan was subsequently defined along the line of sight between

Texcoco and Chapultepec, in such a way that it would perpendicularly intersect a line drawn through the Cerro de la Estrella and to Tenayuca.

The

location of Tlatelolco is even more interesting, in that it is situated along

the axis Cerro de la Estrella – Tenochtitlan – Tenayuca, and also marks the

point in which a line of sight drawn from Teotihuacan to the Cerro de Chapultepec

intersects this latter axis.

|

| The final picture of all the major alignments and lines of sight discussed in the present article. The major triangles and geometric figures are highlighted in different colors. The base of the triangle having Texcoco as its center (highlighted in red), marked by the axis Chapultepec-Mount Tlaloc, corresponds to the parallel of latitude at 19° 25´ North. Tenayuca and Cerro de la Estrella are also at the center of two other large triangles (in green), with the Templo Mayor of México-Tenochtitlan located at the (perpendicular) intersection of the lines connecting the centers of these 3 geometric figures. [Reconstruction by Author, courtesy Google Maps] |

This

systems suggests a very advanced (for the time) knowledge

of cartography and trigonometry for the purpose of triangulation, and also

highlights the existence of a network of alignments of sacred sites based on ancient

lines of sight, which has surprisingly gone virtually unnoticed for the past 500 years. It also suggests that the location chosen for some of the major

temples and ancient cities in the valley of Mexico, including the very Aztec capital of

México-Tenochtitlan, is not arbitrary,

but rather the product of an elaborate geodetic scheme that incorporates pre-existing

natural as well as artificial landmarks.

References

[1] The Board of Longitude, established in 1714, rewarded John

Harrison for the invention of the marine chronometer in 1773. Before that,

longitude could only be crudely determined with the so called “Lunar distance method”, first devised by Galileo Galilei in

1612, who noticed that the relative positions of the Moon and Jupiter could be

used as a sort of universal clock; a method which however required accurate

knowledge of their orbits and cycles.

[2] The

chief archaeologist and director of excavations at Tlatelolco, Salvador

Guilliem, even goes to the point of suggesting that these three pyramids, those

of Tlatelolco, Tenayuca and Tenochtitlán, bear such close similarities to each

other that can only be explained if they were erected by the same builders.

Descubren en Tlatelolco Pirámide más antigua que Tenochtitlán, in La Jornada, 27/12/2007,

accessed on-line: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2007/12/27/index.php?section=cultura&article=a04n1cul

[3] Enrique Juan Palacios, La Orientación de la Pirámide de Tenayuca y el principio del año y

siglo indígenas, Contribución al XXV Congreso de Americanistas de la

Plata, Buenos Aires, 1932. Accessed on-line:

http://www.revistadelauniversidad.unam.mx/ojs_rum/files/journals/1/articles/4006/public/4006-9404-1-PB.pdf

[5] William Bullock, Six Months Residence and Travels in Mexico, London, 1824, p.

383-395