|

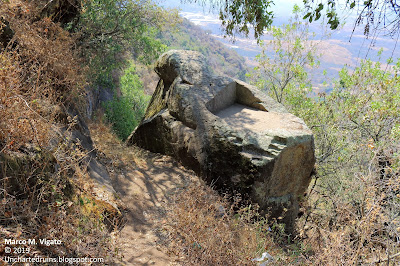

| The summit of the monolithic pyramid known as the Cama de Moctezuma on the Cerro de la Malinche in Acatzingo de la Piedra, Mexico. [Photo by Author] |

Acatzingo de la Piedra is an ancient fortified hilltop site in the municipality of Tenancingo, Mexico. It is located approximately 50 kilometers to the south of the state capital of Toluca and 100 kilometers to the southwest of Mexico City, near the Nevado de Toluca volcano.

The site has never been excavated, but has been mapped and described in a 2010 publication by archaeologist Beatriz Zúñiga Bárcenas of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), and more recently by archaaeologist Vladimira Palma Linares of the UAEM Tenancingo.

The site is one of only five known across Mexico to display significant examples of monolithic rock-cut architecture (the other four being Tezcotzingo and Malinalco, also in the state of Mexico, and the rock-cut shrines of Mazatepetl and Chapultepec in Mexico City).

The ascent to the fortified citadel is possible through a trail that starts in the village of Acatzingo de la Piedra, along massive basalt cliffs offering breathtaking views of the valley of Toluca. The cliffs provided a natural defense for the site, and were complemented with defensive terraces and stone walls.

|

| The imposing basalt cliffs surrounding the site on three of its four sides. [Photo by Author] |

|

| Aerial view of the site of Acatzingo, protected by massive cliffs. [Photo by Author] |

In places the exposed rock surface gives the appearance of an immense megalithic wall formed of huge cyclopean stones. The effect is indeed so strong that one wonders if some portions of the cliff face are not in fact ancient and very eroded stone walls, whose blocks appear to be carefully laid one on top of each other in regular rows.

|

| Is this just some strange geology or ancient megalithic stone walls? [Photo by Author] |

|

| More strange geology - Several huge stone boulders seemingly forming part a continuous megalithic stone wall. The question is - Natural or artificial? [Photo by Author] |

Walking along the cliff face, one passes an impressive and nearly vertical rock tower before reaching a portion of what appears to be another megalithic stone wall (or unusual geology?) on which a bas-relief of a goddess, probably Chalchiuhtlicue, but also identified with La Malinche, was carved during the Aztec (Late Post-Classic) period. The identification of the bas-relief with Chalchiuhtlicue, the goddess of terrestrial waters, seems appropriate given the presence of a natural spring gushing forth from behind the rock nearby.

|

| A massive rock pinnacle or tower on the approach to La Malinche. [Photo by Author] |

|

| Bas-relief carving of the goddess Chalchiuhtlicue, near a natural water spring on the Cerro de la Malinche. [Photo by Author] |

|

| A detail of the same carving with calendrical glyphs symbolically relating to the beginngin of the present World Age or Cycle and the New Fire ceremony celebrated every 52 years. [Photo by Author] |

|

| More unusual geology near the carving of the goddess Chalchiuhtlicue. The cliff face has the appearence of an ancient and very eroded megalithic wall of interlocking stone blocks. [Photo by Author] |

|

| Petroglyphs painted in white on the cliff face, including crosses and monograms, testifying to the colonial use and occupation of the site. [Photo by Author] |

A perilous trail then leads along the edge of the cliff to an area of petroglyphs drawn in bright white on the rock face. The petroglyphs, mostly crosses, are almost certainly colonial in origin and do not appear to be of any great antiquity. We could not identify the location of another group of petroglyphs (these certainly prehispanic) described by Dr. Zuñiga in her 2010 paper, as the thick vegetation made the trail completely impassable.

One then reaches the base of what is perhaps the most significant monument of the entire site, known as Moctezuma's bed or "Cama de Moctezuma". As seen from below, it has the appearance of a massive carved monolith of gray andesite, rising in steps towards an irregular and partially flat-topped summit. The overall shape of the rock is quite irregular, with a trapezoidal base some 15 meters wide rising in at least 5 steps that narrow towards the summit, forming narrow ledges between them.

|

| The monolithic pyramid known as the Cama de Moctezuma as seen from the narrow trail below. [Photo by Author] |

|

| Another view of the base of the same pyramid with carved steps. [Photo by Author] |

More carved stone steps, each about 1 meter to 1.5 meters high, are also visible on the face of another huge rock monolith located about 20 meters downhill from the level of the "Cama de Moctezuma", suggesting that this is in fact a much larger, partially buried and likely unfinished structure.

As seen from the air with the aid of a drone, the area appears almost horseshoe shaped, with the largest pyramidal monolith occupying the center of it.

The monolith itself was apparently separated from the natural bedrock by means of a deep-cut trench with nearly vertical walls, in which additional ledges and other carved steps are visible. This trench is now entirely filled with dirt, so that it is impossible to determine at present the depth at which lies the base of the monolith, or if other carvings are present below ground level.

The top of the monolith contains a rectangular depression 1.42 wide by 2.28 meters long, deeply carved into the natural bedrock and seemingly approached by two flights of stairs placed at a ninety degree angle with respect to each other. There we measured an azimuth of 104° E, which may be of astronomical significance.

It is possible that the entire structure was never completed and remained unfinished. It is also possible, however, that its present appearance is due to deliberate destruction during colonial times.

|

| Some more indentations or steps on one side of the monolith. [Photo by Author] |

|

| A deep rock-cut trench separates the monolith from the surrounding bedrock. [Photo by Author] |

About one hundred meters to the south of this rock we found another partially buried stone covered in petroglyphs belonging to different historical periods. Among them we could observe a typical Aztec round shield, or chimalli, two coyote heads, a skull, two circles, a ceremonial knife and a flower. We also observed a petroglyph containing the depiction of a horse, evidence of the late occupation of the site during the early colonial period. The area where the petroglyphs are found appears to have been used as a megalithic stone quarry, from which some huge roughly hewn boulders were extracted. In many places it is possible to observe the holes made in order to splinter the huge boulders into smaller pieces.

|

| A huge half-buried stone covered in petroglyphs in the southern part of the site. [Photo by Author] |

|

| A colonial petroglyph containing the depiction of a horse. Unlike the other prehispanic petroglyphs, this is much shallower and was likely realized with the use of metal tools. [Photo by Author] |

|

| Aztec petroglyphs showing a skull, two coyote heads and a figure of possible astronomical significance, likely a star or a comet. [Photo by Author] |

|

| An area of the megalithic stone quarry with huge partially finished and carved stone boulders near the southern portion of the site and the petroglyph rock. [Photo by Author] |

The summit of the hill was originally occupied by a set of plazas and pyramids, now entirely reduced to rubble. These structures all seemingly date to the Post-classic period and would have been still in use at the time of the Spanish conquest.

|

| The near flat summit of the Acatzingo hill, showing remnants of low stone platforms, mounds and retaining walls, now much destroyed and largely overgrown. [Photo by Author] |

Acatzingo is a fascinating site that contains what appear to be the remnants of two different styles and possibly also different epochs of construction: One megalithic, characterized by the use of massive cyclopean stones and carved rock surfaces; the other characterized by the use of much smaller stones employed for the construction of ceremonial platforms, habitational terraces and retaining walls.

References:

[1] Beatriz Zuñiga Barcenas, "Registro y delimitación del sitio arqueológico del cerro de La Malinche, Acatzingo de la Piedra, Tenancingo, Estado de México", Arqueología, 45, 2010, pp. 212-233.

[2] Roberto Vázquez, "Rescate de la Historia: Exploración del Sitio Arqueologico de La Malinche", Criterio Noticias, June 25, 2019. On-line resource: "https://criterionoticias.wordpress.com/2019/06/25/rescate-de-la-historia-exploracion-del-sitio-arqueologico-la-malinche/. Las accessed March 9, 2021.

[3] Julio César Ortega Velzaquez, Descripción arquitectonica del sitio La Malinche, en el Posclásico Tardío, Tenancingo, Estado de México, UAEM Tenancingo, 2013. On-line resource: http://ri.uaemex.mx/bitstream/handle/20.500.11799/40544/TESIS.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Last accessed March 9, 2021.

[4] Vladimira Palma Linares, "Arqueología en el sitio La Malinche", Revista Universitaria, UAEM, Vol. 2, no. 15, 2019, pp. 22-23. On-line: https://revistauniversitaria.uaemex.mx/article/view/12783/10015. Last accessed March 9, 2021.